Erasing A Blank Slate

There's no liberal mass delusion, only a conservative lack of imagination.

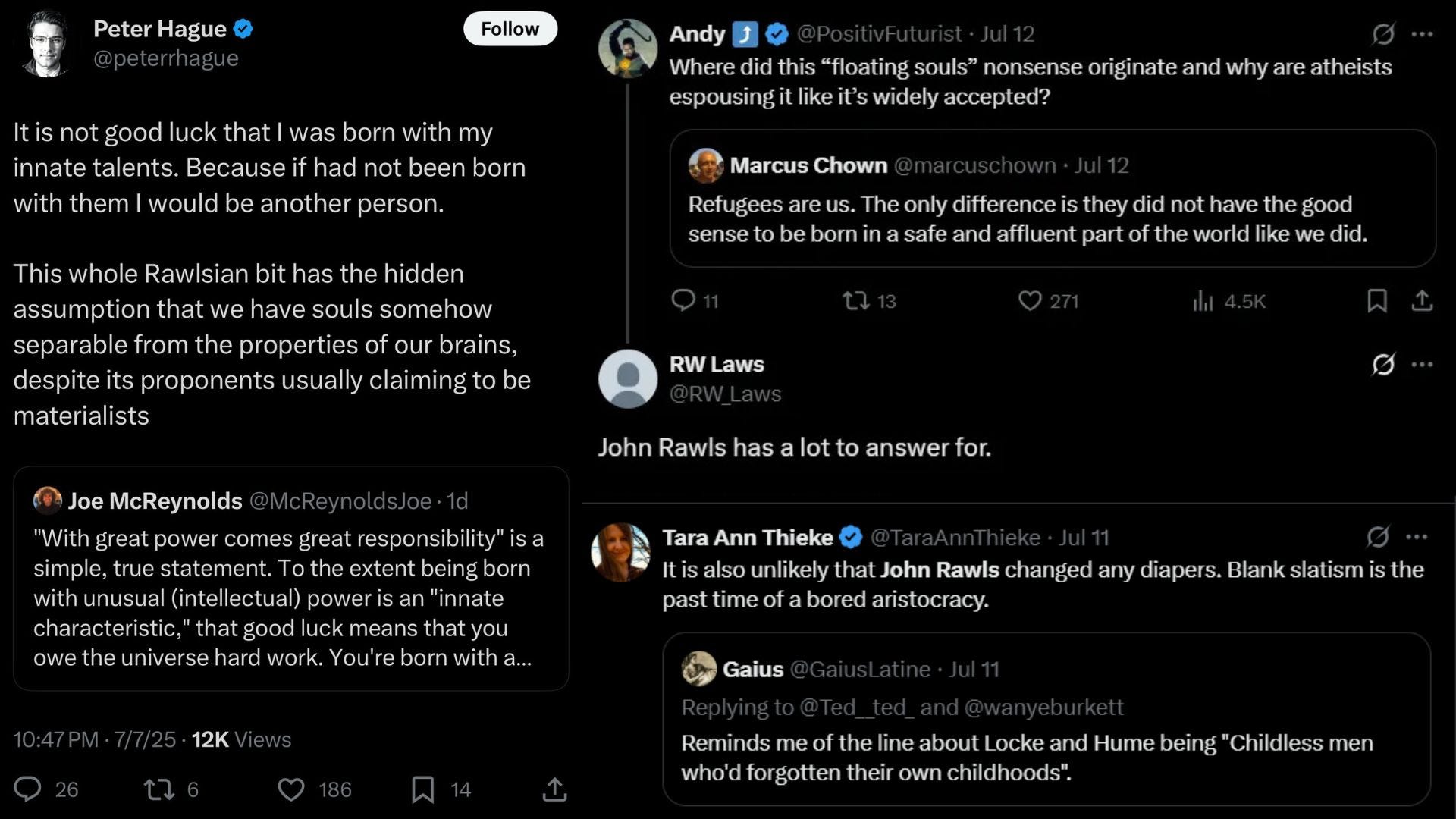

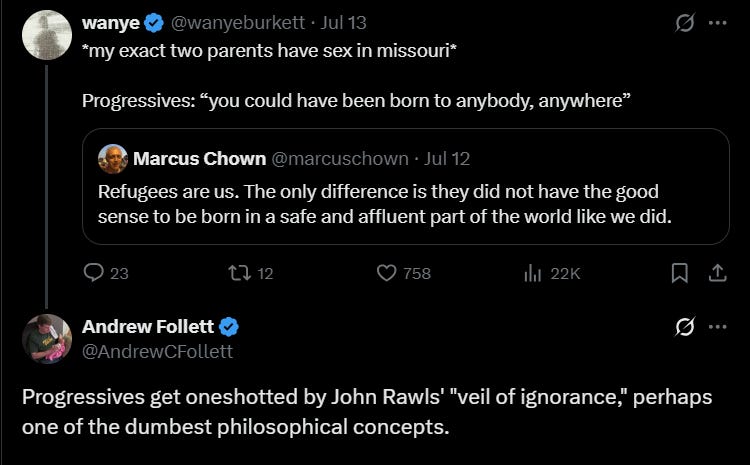

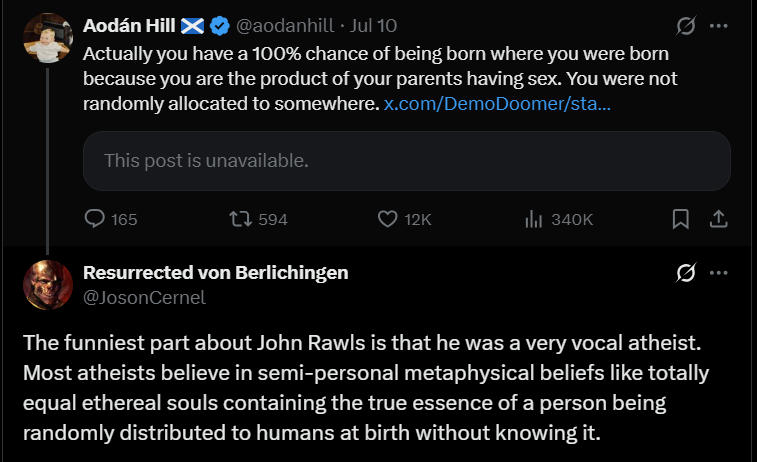

If you’ve spent much time on the right wing side of the internet recently, you’ve probably come across a troubling situation: liberals and leftists are confused about how being a person works. The center left, it seems, has not just forgotten “what a woman is,” or “what marriage is,” but the very nature of human reproduction and identity. According to conservatives, liberals believe that “you could have been born to anybody, anywhere.” They don’t seem to understand that if you “had not been born with [your particular innate talents, you] would be another person.” Sometimes labelled “blank-slateism,” the argument runs that beginning with liberal-egalitarian John Rawls, the left has premised their ideas of fairness and equality on the proposition that anyone could be born as anyone else. There’s good news and bad news for critics of this theory. The good news is that, as laid out above, blank-slateism is a false, illogical, and even absurd doctrine for constructing your political beliefs. The bad news is that no one really believes it.

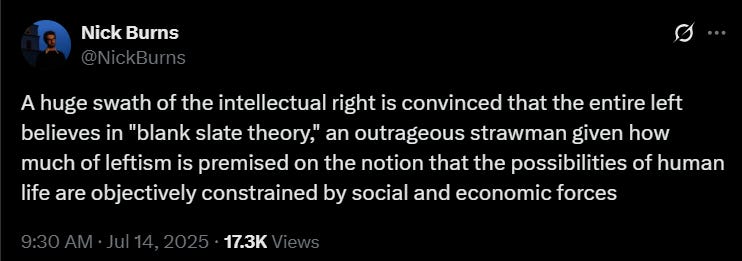

I’m not the only one who’s noticed this idea picking up steam in conservative circles. Nick Burns, associate editor at the Hedgehog Review, has pointed out that a “huge swath” of the right has convinced themselves of this mass liberal delusion.

Here are some obvious facts that blatantly contradict blank slate theory: the only people who could have been my mom and dad were my mom and my dad. I am the biological product of their sexual reproduction, and many of my particular characteristics and traits are the expression of the genetic code determined by the particular sperm and egg cells that I grew out of. What’s more, my identity has been conditioned by the web of connections and abilities that being born to my particular parents made possible and in some cases necessary. No one else could have my particular arrangement of brothers and sisters, hometown and summer camp, friends and first loves. Not only that, but if I did not have them, if I wasn’t embedded in the particular network of conditioned experience that constitutes my life, then in a very serious way, I would not really be myself.

But now new questions emerge: if all of these facts are obvious, even to me, a political egalitarian, what accounts for conservatives’ widespread belief that liberals are getting them completely wrong? What has led them to believe that a prominent philosopher like John Rawls, writing from Harvard in the second half of the twentieth-century got them completely wrong?

The answer appears to be that opponents of blank slate theory are unable, or unwilling, to engage their capacity for perspectival imagination. To understand what I mean by perspectival imagination, and to show how wrong conservatives who treat John Rawls as the architect of blank-slateism are, it will be useful to begin with an intuitive example before we move on to abstract philosophy.

Imagine you’re playing monopoly with a group of friends, and you, by random draw, are using the dog as your player token. If you suggested to your friends that you play this game of monopoly with an additional rule, where the player with the dog token gets to play twice per round, or starts with twice as much money as every other player, no one would take it seriously. It’s a bad way to design the game, because who gets to be the dog is arbitrary. That would be our position even if, instead of random selection, every player chooses their own player token, and you have been a dog-lover since infancy. Your friends might say, in a metaphorical kind of way, “that rule is unfair, because anyone could be the dog,” We would find that reasonable even if they all knew, as a matter of fact, that you would never choose anything other than the dog as your token. Your friends wouldn’t accept that rule even if they knew that if you chose something other than the dog as your token you would not be being yourself. They might even go so far as to suggest that the fact that it’s so closely tied to your identity, rather than anyone else’s is exactly why it’s a bad rule-change. Your friends might suggest that the best way to make the rules of monopoly is to pretend as though you don’t know which token you’ll be, even if deep down, everyone does.

Rawls’ work is filled with big ideas, but its most famous is probably the “original position,” and its associated idea, the “veil of ignorance,” don’t rely on reasoning that are much more complicated than our thinking about monopoly rules. Put simply, the original position is a thought experiment where parties with equal power come together to agree on principles of justice that will organize their common social institutions (the constitution, laws, courts, government bodies, electoral processes, etc.) Importantly, this bargain takes place behind a veil of ignorance in which no individual party knows the particular circumstances of the people that they represent. Not their social position nor race nor gender nor natural ability. Instead, they only have access to general facts: social theory, political philosophy, the events of human history, facts about economics, the moral powers of democratic citizens, and so on. In this position, Rawls argues, the parties will select two principles of justice that he calls “justice as fairness:”

(a) Each person has the same indefeasible claim to a fully adequate scheme of equal basic liberties, which scheme is compatible with the same scheme of liberties for all; and

(b) Social and economic inequalities are to satisfy two conditions: first, they are to be attached to offices and positions open to all under conditions of fair equality of opportunity; and second, they are to be to the greatest benefit of the least-advantaged members of society (the difference principle).1

These principles are accepted on the basis that they best reflect the object of unanimous agreement in the original position. They are chosen over utilitarianism, for example, because parties in the original position would not accept a principle of justice that might require their basic liberties to be sacrificed in favor to maximize the utility of the society as a whole. If the parties don’t know who they’re representing, they can’t accept principles that might allow for their interests to be steamrolled in the name of the greater good (just like your friends can’t agree to rules that favor the player with the dog).

You may notice: none of the preceding argument relies on contradicting the obvious facts I laid out above. That’s because the original position is not, and was never intended to be, a real-life agreement between living human people. Instead, it’s what Rawls called a “device of representation,” or a thought experiment.2 Another way to conceive of it is as an exercise of our imaginative capabilities.3 The original position represents the proper perspective to adopt when reasoning about justice. We imagine how negotiation between parties behind the veil of ignorance would go because it captures fundamental ideas we have about political justice itself: that the composition of our genotype should not effect what basic rights we have, that our opportunities for education shouldn’t be determined by our heritage or caste, that our personal religious beliefs can’t be used to justify an infringement on freedom of speech, and so on. The original position isn’t an argument that we could literally become someone else, but a manifestation of the familiar notion that there are things about us that the government can’t make use of to deprive us of our liberty or threaten our equality as citizens.

This notion is what progressives are getting at when they suggest in figurative language that you “could have been born as someone else:” that features of your identity that are particular to you don’t make for good inputs into our view of political justice, because they don’t always apply to someone else. But recognizing the fact that your natural talents and particular life circumstances are arbitrary from the perspective of justice is not to argue that they are random from the perspective of the individual to whom they belong. Ultimately, this is a distinction we make regularly in everyday life when we debate how to sett up the rules or principles of a collective endeavor, from politics to monopoly.

The intuitive character of this kind of argument raises a new question: how is it possible that conservatives find them so illogical? I’m hesitant to go here; I prefer not to make arguments about the character or capacity of my interlocuters and risk launching a mere ad hominem attack. But there seems no other way to account for how this argument has been mangled so badly in translation that conservatives attack a position virtually no one holds.4 My sense is that the anti-blank slateist conservatives at issue in this essay simply refuse to imagine what kind of reasonable arguments their opponents have that convinced them of a different normative perspective. In fact, the very idea of a different normative perspective seems to be beyond the imaginative range of many of these folks. The suggestion that people might adopt a political point of view that weighs the concerns of others on par with their own, let alone that people might exclude some of their own interests as a matter of justice, seems to strike many conservatives as so bizarre that they prefer to invent a factual disagreement to explain the divergence in points of view instead. They seem to begin with the conclusion that only full-blown idiots could ever say what liberals say, and go on to invent whatever premises will make it so afterwards. But that’s only armchair speculation, and surely many involved in this debate are merely confused.

None of this is to say that that Rawlsian liberal-egalitarianism, or intuitive arguments which are similar to it, are immune to criticism. Philosophers like G.A. Cohen and Amartya Sen have developed highly influential criticisms of justice as fairness, among many others. The difference between them and the conservative critics of blank-slate theory discussed in this essay is that Cohen and Sen aim at Rawls’ view as they could best and most generously understand them.

Imagination is an important tool for anyone interested in politics. In my view, it’s an indispensable one. But there’s a difference between imagination and fantasy; between responding to the arguments of your political adversaries, and making them up.

John Rawls, Justice as Fairness: a Restatement (Harvard University Press, 2001), 42.

Ibid., 17.

For a more fleshed-out account of Rawls’ work through the lens of intellectual exercises, see Liberalism as a Way of Life by Alexandre Lefebvre. That excellent book makes use of a more expansive notion of intellectual exercise than I do here.

I add “virtually,” not because I am aware of anyone (progressive or otherwise) that seriously disputes the obvious facts I listed above, but because I don’t want to preclude the possibility that one foolish person or another has attempted to do so. It seems enough, to me, to show clearly that John Rawls cannot be said to have been a blank-slateist, and that many others who have been accused of having done so are making what are in fact rather familiar, intuitive arguments instead.

“But recognizing the fact that your natural talents and particular life circumstances are arbitrary from the perspective of justice is not to argue that they are random from the perspective of the individual to whom they belong.” Well said.

"Importantly, this bargain takes place behind a veil of ignorance in which no individual party knows the particular circumstances of the people that they represent. Not their social position nor race nor gender nor natural ability. Instead, they only have access to general facts: social theory, political philosophy, the events of human history, facts about economics, the moral powers of democratic citizens, and so on. In this position, Rawls argues, the parties will select two principles of justice..."

His principles don't follow because he's not accounting for risk aversion or growth.

1. In the original position, parties who aren't risk averse would want principles of justice that maximize the total utility even if there's a lot of inequality. Rawls insanely just assumes that parties in the OP would be completely risk averse, i.e. that they would only care about the worst-case scenario.

2. In the original position, parties who don't know the year they'll be born would plausibly choose principles of justice that maximize growth, even if inequality increases (including inequality across time, i.e. where people born earlier are worse off than late born earlier).

----------

But really many conservatives would just reject the moral relevance of the OP/veil-of-ignorance arguments, which probably explains the reaction of the right-wing Twitter commenters. For example, if a conversation goes:

"I oppose US aid to Uganda."

"You should support it, because you could have been born in Uganda, in which case you would have supported US aid."

"No, I couldn't have been born in Uganda."

In this case, the RW poster probably rejects the moral relevance of any hypothetical OP contract.

And this makes sense, because contracts that you would have hypothetically made aren't usually considered binding. For example, if you buy a $1 lottery ticket and win $1m, you aren't obligated to concede to my demand that you give me $500k on the grounds that you would have done so before learning the result (i.e. in a hypothetical situation that I've decided is morally relevant).